Questions from Will Jones' interview with Moshe Safdie (June 2017)

Questions from Will Jones' interview with Moshe Safdie (June 2017)

Why sketch? How important is it for an architect to be able to sketch and what is the importance of sketching (physical design methods) to architecture in the 21st century?

How does your sketching/drawing fit within the overall design process and are digital means used to advance the design? If so, do they combine with the sketch or take over from it?

To me, sketching is the basic tool for evolving design concepts, and in later phases of the work, developing details and examining particular design issues in the overall scheme. I have two modes of sketching. One is a large-format, working on trace, sometimes over base drawings or site plans, utilizing charcoal and Othello coloring pencils, which are pastel, smudgeable and soluble in character. I use large-format primarily in the early phases of evolving a design. In plans and sections, charcoal can be rubbed away and redrawn over and over, so that it is malleable and lends itself to evolution of an idea on the same sheet of paper. Colors enhance elements within the design and its organization.

I’m indebted for this technique to Louis Kahn, with whom I apprenticed at the early phase of my career. Kahn’s use of charcoal as a fluid means of the embryonic, and even later phases of design, was contagious.

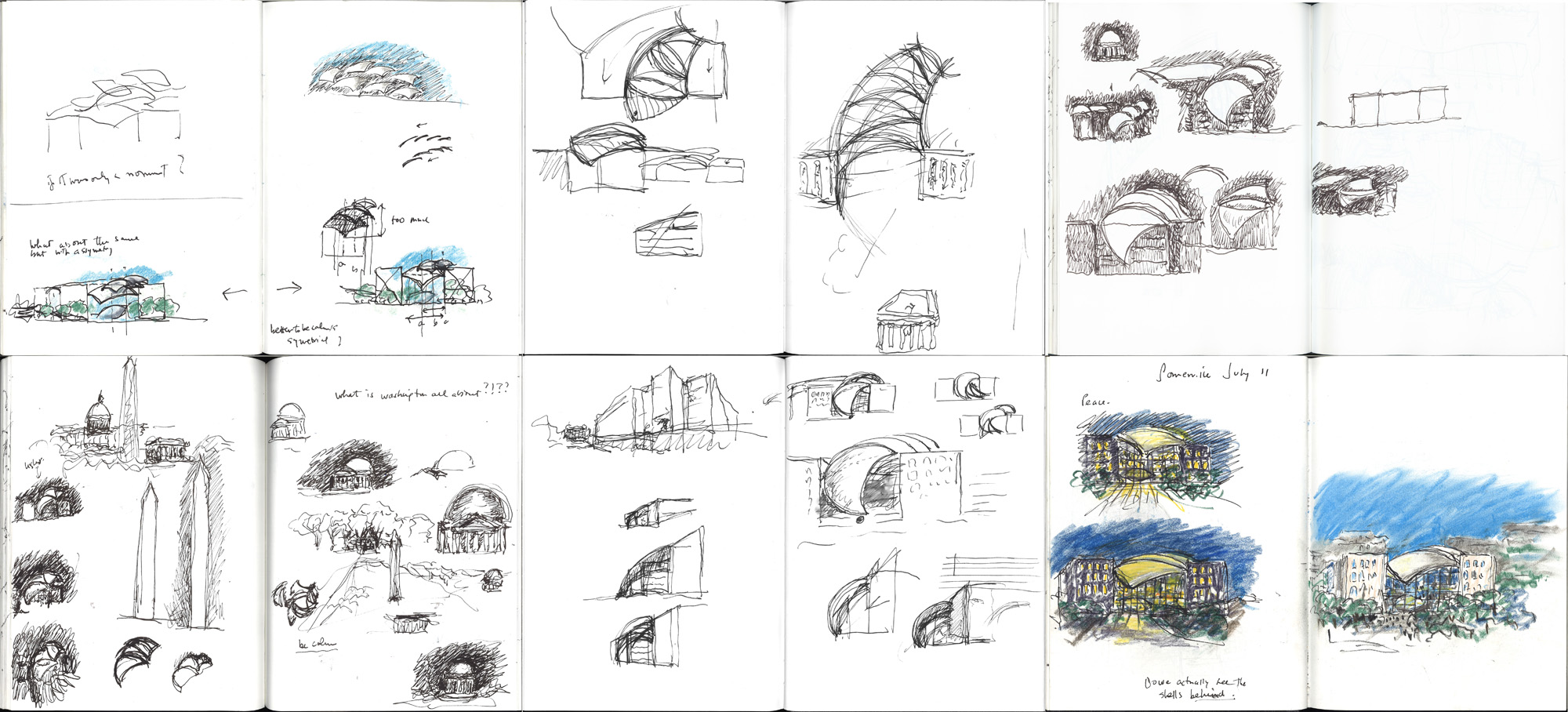

The second mode of design evolution is working with my 8.5’ x 11’ sketchbook, which is always with me, into which I can sink at work, on airplanes, while being transported in cars, even in lounges and waiting rooms. The mode of sketching is pen with ink, sometimes using Othello pastels as well. I have consistently and continuously worked in such sketchbooks for the past 50 years. In all, there are 183 full sketchbooks, typically 100 pages per book. Since I am constantly working on three or four projects at the same time, the sketchbooks are a mélange of project studies at different phases.

The ink drawings are fundamentally different in nature to charcoal, but they are most effective in thinking through building sections, construction details and three-dimensional spaces. I switch often from plan section to 3D axonometric or perspectives, done loosely and without any aides. I tend to annotate the drawings with thoughts and conclusions. Often, I photograph these and forward them to the office for further development. In recent years the design process has been enriched by the back-and-forth, cross-fertilization of my own hand sketches, together with 3D computer studies that are carried out in parallel by the team in the office. Since I travel extensively, sketches are often sent to the office, evolved into 3D, Rhino-type drawings, returned and annotated over and over. In parallel, the workshop begins developing models at various scales, depending on the project, so that we are privy to full, detailed models of the building over time, and the spaces within it. I cannot conceive of the design process without this triangulation.

Today, I feel dependent on my sketches for thinking-through ideas, on the 3D studies for evolving them into tangible geometries, and for the models for understanding the spatial implications of what we are doing.

Sometimes the design effort shifts to the models, as we cut, paste, assemble and take apart a study model and then return to the sketch and 3D drawing mode.

Do you sketch fully formulated ideas or is your sketching a multi-layered/iterative process?

I sketch in every phase of a project: embryonic diagrams in the early phases; developed plans and sections and 3D studies, and even construction details during the construction phase of a project.

How does the physical nature of sketching improve your design work?

How does the physical nature of sketching improve your design work?

The physical nature of sketching does not improve the design. It is the tool for conceiving a design. In later phases, sketching is used to explore every aspect of the design from spatial to construction details. Altogether, for all phases of design, including the technical detailing, sketches are indispensable to me for thinking through the diagrammatic, spatial and technical aspects of a building.

Would you be able to work without sketching or other physical, non-digital, means?

In recent years, after decades of practice, I’m able to think through a building, spatially, without resorting to any physical mode. In other words, while swimming or jogging, I’m able to image the design of a building, examine it spatially and evolve the idea further in my mind. However, at some point, I must put it down on paper. This means that sometimes early sketches already have a rather worked-out character, as the building has been thought-through abstractly.

Since I was not able to do that in my earlier years as an architect, I assume that it is a skill that evolves much as a deaf composer is able to compose a complex work of music without physically hearing it. Eventually, however, it has to be put down in musical notes on paper.

How do clients react to your working methods, and interact with your sketches/drawings/models?

Since my working style is to share ideas in the early design process with clients, in order to precipitate a dialogue and get input, even in the embryonic phases, I share my sketches with the client without hesitation. I recognize that sometimes these are somewhat abstract as tools of design, prepared for the representational character, but I find that it’s nevertheless effective means of communicated early design ideas.

Where do you sketch?

I sketch at home, in the office, in airline lounges and on airplanes; I basically sketch everywhere as I carry a box of colored pencils, my pens and my sketchbook with me always.

What happens to your sketches when the design is complete?

All my sketchbooks and the loose sketches on sheet paper are collected and archived in the Moshe Safdie Archive, which I have donated to and was established by McGill University in Montreal. In recent years, we have scanned all the sketchbooks and separated to each project’s chronology so that they can be studied by those interested.